What Is a HAZOP Analysis?

A HAZOP analysis is a structured, team-based risk identification method used to systematically examine process deviations and their potential consequences.

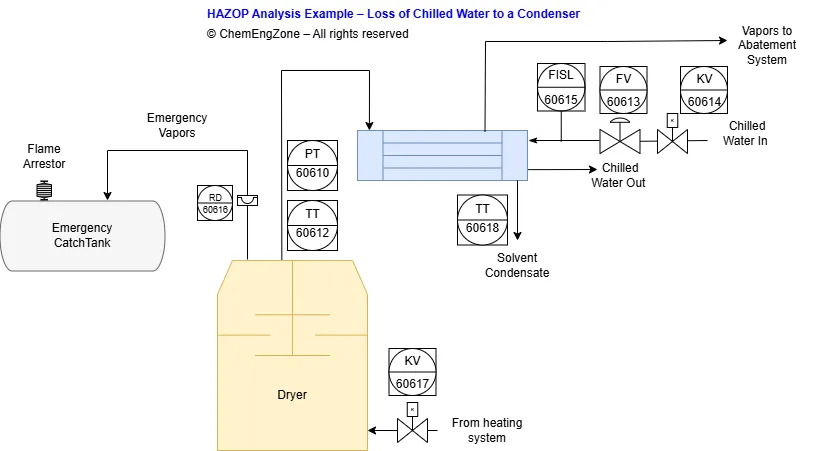

In this hazop analysis example, we will combine theory and practice using a real dryer system with a condenser cooled by chilled water. The goal is not to memorize guide words, but to understand how deviations are generated, how consequences develop, and how safeguards affect risk.

A HAZOP analysis (Hazard and Operability Study) is a structured method used in process industries to identify potential hazards and operability problems caused by deviations from intended operating conditions.

In the context of process hazard analysis, HAZOP does not focus on equipment failures alone, but on how a process may behave when key parameters such as flow, temperature, or pressure deviate from design intent.

How a HAZOP Analysis Works in Practice

A HAZOP analysis starts from the design intent of a process and systematically challenges it using guide words.

Guide words such as No, More, Less, Reverse are combined with process parameters like flow, temperature, or pressure to generate deviations.

Each deviation has to be credible and is then analyzed following a fixed logical sequence: cause, consequence, safeguards, and risk evaluation. HAZOP does not require analysis of all guide word combinations, only those that are technically credible.

Causes explain why the deviation may occur. Consequences describe what happens to the process when a deviation occurs. Severity reflects the potential impact of that consequence in terms of harm to people, assets, or the environment.

In risk evaluation, severity represents the potential impact of the identified consequence and does not depend on safeguards, while likelihood reflects how probable the scenario is, considering the safeguards in place.

This distinction is essential to understand how HAZOP supports sound engineering decisions rather than checklist-based conclusions.

HAZOP Analysis Example: Method Breakdown

The following HAZOP analysis example is based on a dryer system equipped with a condenser cooled by chilled water.

In a HAZOP analysis, the starting point is the definition of the node intent.

The node represents what the process is intended to do under normal operating conditions.

In this example, the node intent is to heat the dryer in order to remove solvent from the product.

During the heating phase, solvent vapors are generated inside the dryer and routed to the condenser. Chilled water is used to remove heat from these vapors, allowing condensation and preventing pressure build-up. The chilled water flow to the condenser is regulated by the flow control valve FV-60613, which modulates based on the signal from the flow indicator and low-flow switch FISL-60615 installed on the chilled water inlet line.

The condensed solvent is collected, while non-condensable vapors are sent to the abatement system. Pressure inside the dryer is monitored by the pressure transmitter PT-60610, and temperature is monitored by temperature transmitters TT-60612 on the dryer and TT-60618 on the condensate line, providing early indication of abnormal operating conditions during the heating phase.

An emergency pressure relief path is provided through the rupture disc RD-60616, which is connected to an emergency catch tank. The rupture disc does not control the process but limits the consequences in case of excessive pressure by providing a defined relief path.

Once the heating intent is defined, the HAZOP analysis focuses on what could go wrong while this intent is being achieved.

In this example, only one parameter is selected for illustration purposes: the chilled water flow to the condenser, since it clearly shows how a deviation can propagate through the system and lead to safety-relevant consequences.

The guide words Less and More are therefore applied to the parameter Flow on the chilled water line, and the resulting deviations are analyzed and recorded in the HAZOP worksheet.

HAZOP Worksheet Example

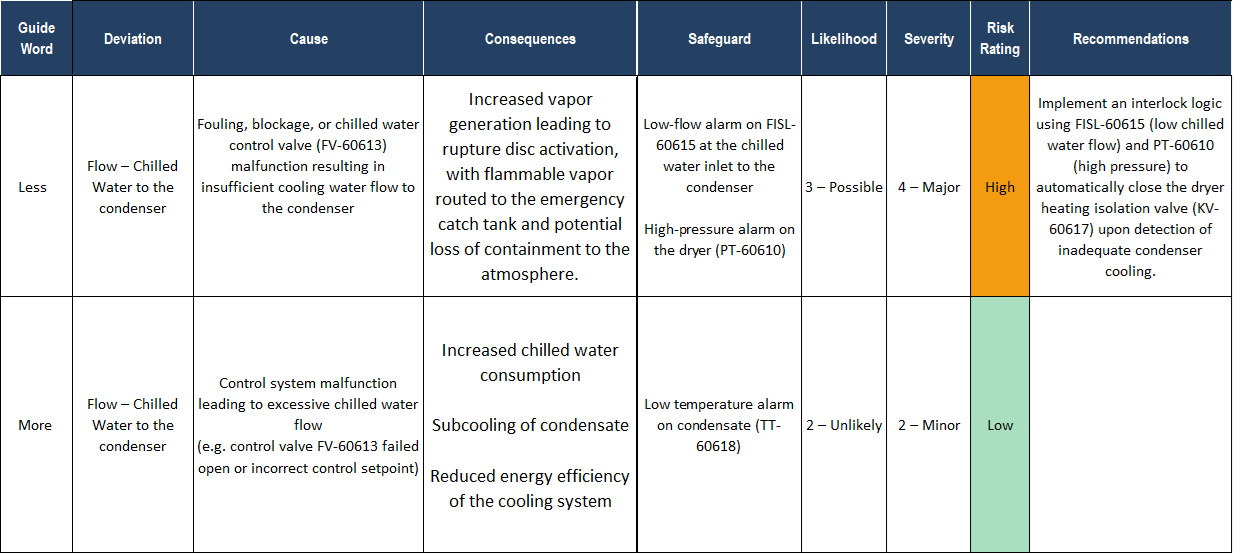

This HAZOP worksheet analyzes deviations related to chilled water flow to a condenser, using two guide words: Less and More.

Each row must be read following the HAZOP logic defined in the guideline: cause → deviation → consequence → safeguards → risk evaluation.

Deviation: Less Flow – Chilled Water to the Condenser

Deviation

The guide word Less is applied to the parameter flow.

This deviation represents a chilled water flow lower than required for normal condenser operation.

Cause

The identified causes are fouling, blockage, or malfunction of the chilled water control valve.

All these causes reduce the effective cooling capacity of the condenser.

Consequence

In HAZOP, consequences describe harm, because hazardous conditions only represent potential sources of damage and do not constitute actual impact on people, assets, or the environment.

In this case:

- the hazard is insufficient condensation leading to increased vapor generation;

- The consequence (harm) is the potential loss of containment of flammable vapor from the catch tank to the atmosphere.

As vapor generation increases, system pressure rises until the rupture disc activates.

The rupture disc performs its protective function by routing flammable vapor to the emergency catch tank.

Depending on system conditions, this can result in potential loss of containment of flammable vapor to the atmosphere.

Safeguards

Existing safeguards include:

- a low-flow alarm (fisl-60615) on the chilled water inlet to the condenser;

- a high-pressure alarm on the dryer.

These safeguards do not prevent the deviation itself because they do not automatically act on the process to stop or limit the deviation.

They only indicate that the deviation has occurred, without modifying process conditions.

Severity

The severity is classified as Major.

Severity is assessed based on the potential consequences of the deviation, without taking credit for existing safeguards.

In HAZOP practice, a Major severity typically refers to scenarios that may involve serious injury or permanent health damage, major equipment failure, environmental release requiring regulatory reporting and containment, and production loss of several days.

In this case, the identified consequence is a potential loss of containment of flammable vapor following rupture disc activation.

Such a release may expose personnel in the affected area to serious safety hazards, may require containment and regulatory reporting, and may result in equipment damage and production interruption extending beyond routine operational disturbances.

For these reasons, the impact clearly exceeds minor or moderate levels and aligns with the definition of Major severity.

At the same time, the scenario does not inherently imply widespread destruction, multiple fatalities, or long-term plant shutdown. These characteristics are typically associated with Catastrophic events and are not assumed here based solely on the deviation under analysis.

The severity is therefore appropriately classified as Major, in accordance with standard HAZOP severity definitions.

Risk Evaluation

The likelihood is assessed as Possible, reflecting that fouling or valve malfunction can reasonably occur during operation.

The severity is assessed as Major, because loss of containment of flammable vapor may lead to significant safety, environmental, and operational impact.

The resulting risk rating is High.

Recommendations and Residual Risk

One possible recommendation could be the implementation of an interlock. to automatically isolate the heating system when low chilled water flow is detected.

This reduces the probability of escalation by preventing continued vapor generation.

After implementation, the likelihood is reduced to Unlikely, while severity remains Major, resulting in a Medium residual risk.

Deviation: More Flow – Chilled Water to the Condenser

Deviation

The guide word More is applied to the same parameter, indicating chilled water flow higher than design intent.

Cause

The causes are control-related: a control valve failing open, incorrect setpoints, or control loop malfunction.

Consequence

The consequence reflects the actual harm associated with excessive cooling:

- increased chilled water consumption;

- subcooling of the condensate;

- reduced energy efficiency of the cooling system.

No flammable release or hazardous condition is created by this deviation.

Safeguards

A low-temperature alarm on the condensate provides sufficient detection of this condition.

Risk Evaluation

The likelihood is assessed as Unlikely and the severity as Minor, since the impact is limited to operational inefficiency and does not affect safety.

The resulting risk is Low, and no additional recommendations are required.

A credible deviation does not necessarily lead to a significant consequence. Deviations with limited impact, such as high cooling water flow, should still be analyzed to confirm that no relevant safety or operability issues exist.

Conclusion

This HAZOP analysis example shows the practical value of the method through the structured reasoning applied during the study.

A clearly defined node intent, the systematic use of guide words, and the clear separation between causes, consequences, safeguards, and risk evaluation allow safety-critical scenarios to be made explicit, traceable, and open to technical discussion within the team.

Ing. Ivet Miranda

Other Articles You May Find Useful

• HAZOP Example: Material Compatibility Failure

• LOPA & SIL: Practical Examples

• The 4 Pillars of a Safety Management System

• Safety Interlocks: P&ID Example

• Chemical Engineer Skills: 2 Field Practices

FAQ

What is a HAZOP analysis?

A HAZOP analysis is the practical application of the HAZOP method, where deviations from normal operation are identified, their causes and consequences are evaluated, and safeguards are assessed to determine whether additional risk reduction measures are required.

Can you give a HAZOP analysis example?

Yes. In this article, a HAZOP analysis example is developed starting from a defined node intent and analyzing two deviations related to chilled water flow to a condenser. The example shows how causes, consequences, safeguards, and risk are evaluated step by step using a real HAZOP worksheet.

Is HAZOP a legal requirement?

HAZOP itself is not universally mandated by law, but it is widely recognized as an acceptable method to comply with regulatory requirements related to process safety. In many industries, performing a HAZOP is considered best practice and is often required by company standards or safety regulations.