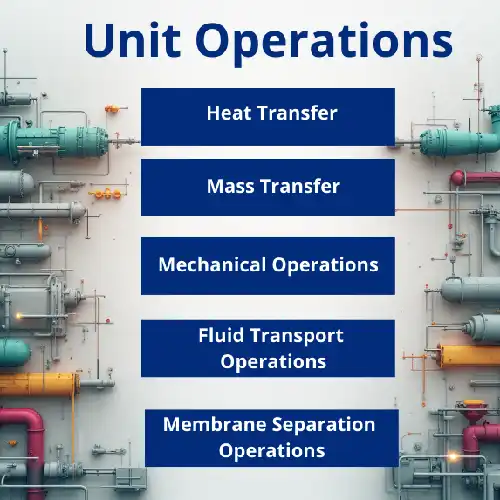

In chemical engineering, a unit operation describes a physical transformation, such as heat transfer, separation, or fluid transport, independent of the specific plant layout. A process unit, instead, refers to a physical section of the plant where one or more unit operations take place, typically involving multiple pieces of equipment.

Introduction

In industrial practice, a chemical plant is not defined by its equipment, but by the physical transformations applied to materials. Heating, cooling, separating, mixing, filtering, transporting — these actions recur across industries, regardless of scale, product, or technology. Focusing only on machines hides the underlying logic of the process.

This page provides a structured overview of the main unit operations used in chemical engineering, organized by function and physical mechanism. Its purpose is to clarify how unit operations fit within the broader framework of chemical engineering practice.

Heat Transfer Operations

Heat-exchange operations are based on the three main modes of heat transfer: conduction, convection, and radiation.

These operations are carried out using specific equipment such as:

shell-and-tube heat exchangers, plate heat exchangers, double-pipe exchangers, and spiral heat exchangers.

Each type is chosen based on fluid properties, available space (some heat exchangers, like shell-and-tube types, can be very large), and process requirements.

Main Heat Transfer Operations

Sensible Heating and Cooling

This operation is used to raise or lower the temperature of a process stream without inducing a phase change. It supports temperature control in reactions, separations, or feed conditioning.

Common equipment includes: shell-and-tube heat exchanger, plate heat exchanger, double-pipe heat exchanger.

Boiling / Reboiling

Boiling or reboiling provides the latent heat required to convert liquid into vapor, typically used in distillation columns and flash vessels to drive phase separation.

Key devices are: reboiler (kettle, thermosyphon, forced circulation types).

Condensation

Condensation involves converting vapor into liquid, usually to recover solvents, enable reflux, or reduce emissions. It is the reverse of boiling and is vital in closed-loop systems.

Typical equipment: condenser (vertical, horizontal, air-cooled or water-cooled).

Evaporation and Concentration

This operation removes water or solvents by converting them into vapor, thereby increasing the concentration of the solute. It is widely applied in purification, drying, and pre-crystallization stages.

Typical equipment: falling film evaporator, rising film evaporator, forced circulation evaporator.

Cooling Crystallization

Cooling crystallisation promotes the formation of solid crystals from a supersaturated solution through controlled cooling. It is used to ensure product purity and uniform crystal size, especially in pharmaceuticals.

Typical equipment: batch crystallizer, draft-tube baffle crystallizer, scraped surface crystallizer.

Thermal Insulation and Heat-Loss Control

This operation aims to minimize unwanted heat loss or gain from equipment, pipes, and tanks to improve energy efficiency and maintain temperature stability across the process.

Typical equipment: insulated vessels, insulated pipelines, jacketed tanks with insulation layers.

Mass Transfer Operations

These operations are often tightly coupled with heat transfer and fluid transport, especially in industrial separation units.

Mass transfer operations are essential for separating and purifying mixtures involving gas, liquid, and solid phases.

These unit operations rely on concentration gradients to move components from one phase to another, such as gas to liquid, liquid to liquid, or solid to liquid.

Processes like distillation, absorption, extraction, and crystallization are all governed by mass transfer principles—most notably Fick’s Law of Diffusion and phase equilibrium.

Understanding these fundamentals enables chemical engineers to select appropriate operations and design efficient separation systems tailored to each application.

Main Mass Transfer Operations

Distillation

Distillation separates components in a mixture based on differences in volatility. It relies on vapor–liquid equilibrium and is widely used in petrochemical, pharmaceutical, and food industries.

Typical equipment: distillation columns, trays (sieve, valve, bubble cap), structured packing, reboilers, condensers.

The operating principles of distillation, from flash vaporization to staged columns, are discussed in detail in How Distillation Works.

Absorption

Absorption transfers a gas-phase solute into a liquid solvent, typically used for gas purification or removal of contaminants.

Typical equipment: packed towers, tray columns, spray columns, gas scrubbers.

Stripping

Stripping removes volatile components from a liquid by contacting it with a gas, usually steam or air. It is essentially the reverse of absorption.

Typical equipment: stripping columns, steam strippers, packed towers, tray columns.

Liquid–Liquid Extraction

This operation separates solutes based on their solubility in two immiscible liquid phases. It is used when distillation is ineffective or thermally unsuitable.

Typical equipment: mixer-settlers, rotating disc contactors, pulsed columns, centrifugal extractors.

Leaching (Solid–Liquid Extraction)

Leaching extracts solutes from solids using a liquid solvent. Common in mining, pharmaceuticals, and food processing.

Typical equipment: agitated leach tanks, percolators, rotary drum extractors, counter-current extractors.

Adsorption

Adsorption captures solutes from a fluid onto the surface of a solid adsorbent, commonly used in gas purification or water treatment.

Typical equipment: fixed-bed adsorbers, moving-bed systems, activated carbon columns, silica gel beds.

Crystallization

Crystallization separates solids from a solution by inducing crystal formation through cooling or evaporation. It is critical for purity and product consistency.

Typical equipment: batch crystallizers, forced-circulation crystallizers, vacuum crystallizers, draft-tube baffle crystallizers.

Mechanical Operations

Mechanical operations include mixing, crushing, filtering, and the handling and transport of solids or slurries.

These processes involve the physical movement and manipulation of materials.

They are widely used in chemical engineering to handle solid–liquid systems and prepare materials for further processing.

Types of Mechanical Unit Operations

Mixing

Combines solids with liquids (slurries) or mixes solid fractions to create a uniform feed for reaction or separation.

→ Typical equipment: Ribbon blender, paddle mixer, high-shear mixer

Filtration

Separates solids from liquids by forcing slurry through a porous medium to form a removable solid cake.

→ Typical equipment: Filter press, rotary vacuum filter, membrane filter

Sedimentation

Allows solids to settle by gravity in order to concentrate them or clarify liquid streams.

→ Typical equipment: Gravity thickener, clarifier tank

Decantation

Removes the clarified liquid phase without disturbing the settled solids.

→ Typical equipment: Decanter, siphon system, overflow weir tank

Centrifugation

Applies centrifugal force to speed up solid–liquid separation, improving clarity and throughput.

→ Typical equipment: Disc-stack centrifuge, decanter centrifuge

Screening

Separates particles based on size to ensure uniformity or remove oversize material.

→ Typical equipment: Vibrating screen, rotary trommel, gyratory sifter

Milling

Reduces particle size for better handling or further processing.

→ Typical equipment: Jaw crusher, hammer mill, ball mill, pin mill

Membrane Separation

Membrane separation operations use semi-permeable barriers to selectively separate particles, solutes, or solvents based on properties such as size, charge, or chemical affinity.

These processes are governed by principles like Darcy’s Law, which describes how fluids flow through porous materials, and diffusion mechanisms, where molecules move from areas of higher to lower concentration.

Membrane separation is widely used in water treatment, bioprocessing, and pharmaceutical production.

The choice of membrane type depends on the molecular size to be retained and the level of purity required for the specific application.

Membrane Separation Technologies

Microfiltration (MF)

Removes suspended solids and microorganisms (0.1–10 µm) from fluids. Common in food and beverage processing, wastewater polishing, and air filtration.

→ Typical equipment: Microfiltration cartridge modules, hollow fiber membranes, ceramic MF units

Ultrafiltration (UF)

Retains macromolecules such as proteins and polysaccharides while allowing water and small solutes to pass.

→ Typical equipment: Hollow fiber UF modules, spiral-wound membrane systems, tubular UF units

Nanofiltration (NF)

Allows monovalent ions (Na⁺, Cl⁻) to pass while rejecting divalent ions (Ca²⁺, SO₄²⁻) and larger organic molecules.

→ Typical equipment: Spiral-wound NF membranes, high-pressure modules, crossflow systems

Reverse Osmosis (RO)

Blocks nearly all dissolved solutes, producing ultrapure water for industrial and pharmaceutical applications.

→ Typical equipment: RO skids, high-pressure RO modules, desalination units

Electrodialysis (ED)

Uses an electric field and ion-exchange membranes to selectively remove ions from a solution.

→ Typical equipment: Electrodialysis stacks, alternating cation-anion membrane units

Membrane Contactors

Facilitate mass transfer between two phases (e.g., gas–liquid) without mixing them. Used for gas removal or capture.

→ Typical equipment: Hollow fiber membrane contactors, degassing modules, CO₂ strippers

Fluid Transport Operations

Fluid transport operations involve the movement, control, and distribution of liquids and gases within industrial plants.

They are applied when fluids pass through pipelines, pumps, compressors, and valves, forming the backbone of most process industries.

Typical equipment: centrifugal pumps, compressors, flow control valves, pipeline networks.

Main Fluid-Transport Unit Operations

Fluidization & Pneumatic Conveying

This operation is used to suspend solid particles in a rising stream of gas or liquid (fluidization) or to transport solids through pipelines using high-velocity gas (pneumatic conveying). These methods are essential for drying, coating, or transferring fine materials like powders.

Typical equipment: fluidized beds, pneumatic conveyors, blowers or compressors, rotary valves (airlocks).

Pumping

Pumping involves transferring liquids from one vessel or unit to another at specific flow rates and pressures. The choice of pump depends on fluid viscosity, pressure requirements, and flow conditions.

Typical equipment: centrifugal pumps, diaphragm pumps, gear pumps, peristaltic pumps.

Pipeline Transport

This operation refers to the movement of fluids through networks of pipes and fittings, accounting for frictional pressure losses, elevation changes, and flow regimes. Engineers must also consider two-phase flow and appropriate material selection.

Typical equipment: piping systems, bends, reducers, expansion joints, pipe supports, two-phase separators.

Valve & Flow Control

Fluid streams in industrial systems must be precisely regulated to ensure process stability and safety. Flow control involves adjusting velocity, pressure, or direction through a variety of mechanical devices.

Typical equipment: control valves (globe, ball, butterfly), pressure-reducing valves, orifices, flow meters (rotameter, venturi, coriolis).

Static Mixing

Static mixing achieves homogeneous blending of two or more fluid streams directly within a pipe, without the use of moving parts. This ensures low-maintenance mixing in continuous processes.

Typical equipment: inline static mixers (Kenics®, Sulzer), helical or tab-type inserts.

Dynamic Agitation

This involves the active mixing of liquids or slurries using mechanical agitators in tanks or reactors. The objective is to ensure uniform concentration, improve heat transfer, or promote reaction kinetics.

Typical equipment: agitated vessels with impellers (Rushton turbines, marine propellers, anchor stirrers), baffles.

Conclusion

Unit operations remain the backbone of chemical engineering practice. Whether dealing with heat exchange, mass transfer, mechanical processing, membrane separations, or fluid transport, every process in industry can be broken down into these fundamental steps.

Ultimately, mastering unit operations means mastering the language of process engineering: the common framework that allows engineers across industries from pharmaceuticals to petrochemicals, from water treatment to food technology, to design, scale up, and troubleshoot complex plants.

Ing. Ivet Miranda

⬆️ Back to TopOther Articles You May Find Useful

• What Is Heat Transfer? Definition and Types

• How Distillation Works: Engineering Explanation

• Fluid Dynamics Basics for Engineers

• The 4 Laws of Thermodynamics

• Chemical Engineering Core Disciplines – A Practical Overview

FAQ

What is a unit operation with an example?

A unit operation is a physical step where materials undergo changes in state or physical properties without altering their chemical structure. Examples include filtration, distillation, centrifugation, and drying.

(Engineering example )

In wastewater treatment, sludge thickening and dewatering are unit operations used to reduce water content before disposal.

What is the difference between a unit operation and a unit process?

As seen above, a unit operation is a physical step in which materials change state, phase, or physical properties without altering their chemical structure.

Examples include filtration, sedimentation, centrifugation, distillation, and drying.

A unit process, instead, involves a chemical or biological transformation that changes the composition or molecular structure of the material.

Examples include oxidation, chlorination, neutralization, and biological digestion.

Example – Sludge Treatment

In wastewater sludge management, both unit operations and unit processes are applied.

Thickening and dewatering (filtration, centrifugation) are unit operations, while stabilization through biological digestion or chemical treatment is a unit process. Together, they transform high-moisture sludge into a stable residue suitable for safe disposal.

What is a unit operation in pharmaceutical industry?

In the pharmaceutical industry, unit operations include essential steps such as granulation, tablet compression, coating, and sterilization.

Each step ensures that the final drug product meets strict quality and safety standards.

What are unit operations in food processing?

In food processing, several steps can be mapped directly to classical unit operations of chemical engineering.

Examples include:

Pasteurizatio: heat transfer (controlled heating to inactivate microorganisms),

Freezing: heat transfer (removal of heat until solidification),

Drying: heat and mass transfer (evaporation of water from the product),

Emulsification: mechanical operation (dispersing two immiscible liquids into a stable mixture).

Other steps, such as packaging, are not classical unit operations in the academic sense (as described in Perry’s Handbook), but are considered essential process stages in food engineering because they preserve product quality, safety, and shelf life.