Principle of Energy Conservation (First Law of Thermodynamics)

The First Law of Thermodynamics—also known as the Principle of Energy Conservation—states that energy cannot be created or destroyed; it can only be transferred or transformed from one form to another.

In thermodynamic systems, this principle is expressed through the energy balance, where variations in internal energy are determined by heat exchanged and work performed. The First Law establishes the quantitative framework required to analyze any engineering process involving energy interactions.

This concept lies at the foundation of chemical engineering thermodynamics and governs all energy-related phenomena in industrial systems, from heat exchangers and turbines to chemical reactors and power generation units.

Modern applications extend far beyond classical heat engines. For example, solar radiation and wind kinetic energy are converted into electrical power in renewable energy systems, illustrating that energy transformation—never creation—is the governing principle.

Access the FREE PDF – Thermodynamics Overview

Download a two-page A3 visual summary covering the key concepts of thermodynamics: energy, work, heat transfer, and the fundamental thermodynamic laws. Designed to help you fix the concept quickly.

Continue to Access the PDFMathematical Form – First Law of Thermodynamics

The First Law of Thermodynamics is represented by the following mathematical equation:

ΔU = Q – W

This equation expresses three essential concepts:

- It provides the general mathematical statement of energy conservation for any process.

- It establishes the existence of the internal energy function U.

- It formally defines heat (Q) and work (W) as energy in transit, not properties of the system.

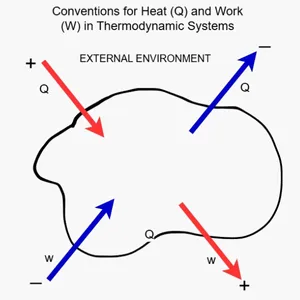

The adjacent figure shows a classic representation of a thermodynamic system. It illustrates the sign conventions for heat (Q) and work (W) in relation to the external environment.

Sign Conventions

- Q>0: the system absorbs heat

- Q<0: the system releases heat

- W>0: the system performs work on the surroundings

- W<0: the surroundings perform work on the system

These conventions allow a consistent application of the First Law to all engineering systems.

In thermodynamics, work is considered an ordered form of energy because it can, in principle, be entirely converted into other useful forms. Heat, instead, is a disordered form of energy and cannot be completely transformed into work in a cyclic process. This asymmetry between heat and work is formalized by the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

The Joule Experiment

(applying the Thermodynamics 1st Law)

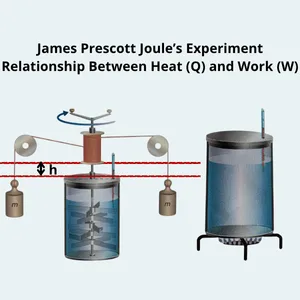

Consider a non-cyclic transformation where a system changes from an initial state to a different final state—for example, heating 1 kg of water from 15 °C to 100 °C.

This temperature rise can be obtained in different ways:

- by directly supplying heat, or

- through mechanical work, such as the stirring mechanism in Joule’s device.

In Joule’s experiment, falling weights rotate paddles immersed in water. The mechanical motion is converted into thermal energy, increasing the water temperature.

From this experiment, Joule established the mechanical equivalent of heat, approximately 4.186 J per cal.

This means that the same amount of energy—supplied either as mechanical work or as heat—produces the same temperature increase, for example raising the temperature of 1 g of water by 1 °C.

The crucial conclusion is:

- Q and W depend on the path of the transformation.

- Their difference, Q−W, does not.

This shows that internal energy U is a state function, depending only on the initial and final states: ΔU=U2−U1.

Substituting, we return to the First Law: ΔU=Q−W

This relationship is valid for any process, regardless of how heat or work are exchanged.

Why a System Must Operate in a Cycle to Produce Work Continuously

Because internal energy is a state function, a system cannot keep producing work indefinitely unless it returns to its initial state.

Only a cyclic process allows:

- the repetition of the same sequence of transformations,

- and therefore the continuous production of work.

Impossibility of a Perpetual Motion Machine of the First Kind (PMM1)

Based on the logical analysis of equation (1), it is possible to state the technical and conceptual impossibility of a Perpetual Motion Machine of the First Kind (PMM1)—a hypothetical device capable of delivering continuous work output without any energy input.

In fact, if a machine were to produce work without absorbing heat (i.e., with Q = 0), the First Law of Thermodynamics would give:

ΔU = –W

And if ΔU = 0, then:

0 = –W ⇒ W = 0

Therefore, no work can be produced without energy input, confirming the impossibility of PMM1.

Common Energy Transformations in Industrial Systems

Chemical Energy

Stored in fossil fuels like oil or gas. This is the energy contained in the molecular bonds of the fuel.

Thermal Energy

When the fuel is burned, its chemical energy is converted into thermal energy (heat), which is used to produce steam.

Mechanical (Kinetic) Energy

The steam spins a turbine, converting thermal energy into mechanical energy (rotational motion).

Electrical Energy

The turbine drives a generator that converts mechanical energy into electricity.

Sound Energy (or other outputs)

The electrical energy powers devices—like a guitar amplifier—that transform electricity into mechanical vibrations and ultimately into sound.

Conclusion

The First Law of Thermodynamics establishes the conservation of energy and defines the quantitative framework used in every engineering energy balance.

Through Joule’s experiment, it becomes clear that heat and work are equivalent forms of energy transfer, and that internal energy is a state function independent of the transformation path.

This principle excludes the possibility of a perpetual motion machine of the first kind and confirms that no system can produce work without energy input.

However, while the First Law guarantees that energy is conserved, it does not determine the direction of processes or the limits of efficiency. These constraints are introduced by the other thermodynamic laws, which together define the complete physical framework of energy systems.

For a structured overview of the entire framework, see The Laws of Thermodynamics: Meaning and Principles.

Ing. Ivet Miranda

⬆️ Back to TopFirst Law of Thermodynamics Quiz

Why was Joule’s paddle-wheel experiment important for the First Law of Thermodynamics?Other Articles You May Find Useful

- Thermodynamics for Engineers

- Thermodynamics Work in a Transformation

- How Distillation Works – A Simple Explanation

- What Is Chemical Engineering and How It Shapes Everyday Life

- Bernoulli’s Principle: Equation & Applications

- Fluid Dynamics Basics for Engineers

- Heat Exchanger Fouling and Rubby Formation

- Unit Operations for Chemical Engineers

FAQ

What is a Thermodynamic System?

A thermodynamic system is a defined portion of matter or space selected for analysis, where energy exchanges (in the form of heat or work) are studied. Everything outside the system is considered the surroundings.

What is Thermodynamic Equilibrium?

It’s the state in which no net flow of energy occurs within the system or between system and surroundings—mechanical, thermal, and chemical balances are all satisfied.

What is Thermodynamics in Physics?

Thermodynamics is the branch of physics that studies energy, heat, and work interactions, and the laws governing their transformations in macroscopic systems.

What is Thermodynamics in Biology?

Thermodynamics in biology explains how energy is produced, transferred, and used in cells—like in ATP production and metabolic pathways.

What is Thermodynamics with Example?

Thermodynamics is the science that studies how energy is transferred and transformed, especially in the form of heat and work. A classic example is Joule’s experiment, which showed the equivalence between mechanical work and heat.

What is a Thermodynamic Cycle?

It’s a series of processes in which a system returns to its initial state. Examples include the Carnot and Rankine cycles in engines.