What skills does a process engineer need?

Being a young process engineer means entering a world that is technical, dynamic, and incredibly formative — especially during your first years on the job.

In many plants, the process engineer is primarily responsible for working with the Distributed Control System (DCS): monitoring trends, adjusting production parameters, managing recipes, and troubleshooting process deviations.

In this document, I’d like to share some first-hand insights from my field experience — highlighting opportunities to grow your leadership and technical mindset.

These are not fixed rules, but practical suggestions for those who want to become well-rounded professionals, capable of going beyond data analysis to truly excel as process engineers in real plant environments.

We’ll cover:

- why limiting your role to the control room hinders your technical growth,

- what it really means to “know the plant” — and how field experience helps build that knowledge,

- how to take initiative when tasks are not clearly assigned,

- what to do when something doesn’t match the P&IDs — and how to verify it responsibly,

- how to communicate findings professionally, especially in cases involving missing safeguards or undocumented changes,

A useful mindset to adopt early on is to take initiative, even when no one is giving you clear direction. As a process engineer, field experience, active observation, and critical thinking are essential — especially if you aim to grow into roles with greater responsibility.

Look Beyond the Control Room

When you first start working as a process engineer, it’s easy to believe that your main job is to monitor process trends through the DCS and manage production recipes from behind a desk.

In many companies, there’s an implicit idea that operations or production engineers are the ones who truly “own” the plant, while the process engineer is expected to take a more analytical, detached role.

In the world of process engineering, curiosity and field experience are two essential qualities that can make the difference between being a good engineer and becoming a great professional.

Curiosity drives engineers to ask “why” things work the way they do, not just “how.” It leads to better problem solving, continuous learning, and a genuine drive for improvement. A curious process engineer doesn’t just follow standard procedures — they seek to understand the reasoning behind them, often uncovering opportunities for innovation or optimization.

Field experience is equally important. Spending time in the plant, observing operations firsthand, and interacting with technicians and operators gives engineers a practical perspective that cannot be gained from the control room alone. It’s where theories meet reality.

If you really want to understand how a process works, the best thing you can do is go into the field.

Ask for the latest P&IDs, print them, and walk the plant to locate every instrument, valve, and pump. At first, it might feel overwhelming — a maze of lines, bypasses, and signals — but that’s where real learning begins.

It’s also where many technical skills are strengthened, like interpreting diagrams in context, understanding instrumentation layout, and connecting process behavior to physical equipment.

Even as your responsibilities grow, try to set aside at least one hour each day to walk the plant. Focus on one detail at a time: a line, a pump, a vessel.

This habit will not only deepen your technical understanding, but also strengthen your relationships on site.

Technicians, maintenance teams, and managers will start to recognize you as a process engineer who truly knows the plant — not just from the documents, but from direct experience.

What is a P&ID?

A P&ID, or Piping and Instrumentation Diagram, is a detailed engineering drawing that shows the physical and functional relationships of piping, equipment, instrumentation, and control systems in a process plant.

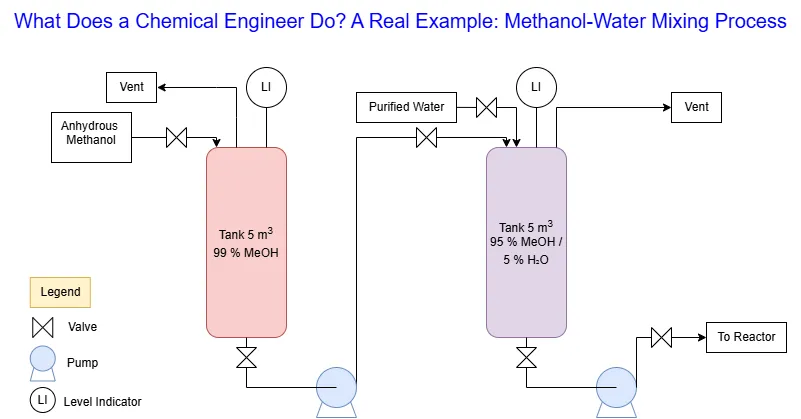

The image above is a simplified example of a P&ID, illustrating a methanol–water mixing process.

It shows two tanks, pumps, valves, and basic instrumentation — a great starting point to understand how elements are represented and connected.

In real industrial environments, P&IDs are often much larger and more complex, covering dozens of equipment items, multiple utility and process lines, safety systems, and automation logic. A single unit may require multiple sheets to represent the full system.

What does a P&ID include?

A typical P&ID contains:

- Pipes and flow directions

- Valves (manual, control, safety)

- Equipment such as pumps, vessels, heat exchangers, and reactors

- Instrumentation (e.g., pressure transmitters, flow meters, level indicators)

- Control loops, interlocks, alarms

- Tag numbers and line specifications

Why is it important?

P&IDs are essential tools for:

- Designing and reviewing process systems

- Performing safety analyses like HAZOP

- Operating and maintaining industrial plants

- Ensuring cross-functional understanding among engineering, operations, and safety teams

How These Qualities Can Shape Your Path to Leadership

Both curiosity and field experience are not only essential for technical growth — they are also powerful enablers for those who aim to move into management or leadership roles.

A curious process engineer who proactively seeks to understand the “why” behind decisions is more likely to develop a strategic mindset. This mindset is crucial for managers who must make informed choices, anticipate risks, and drive continuous improvement.

Likewise, engineers who spend time in the field develop credibility, communication skills, and a deep understanding of how teams operate in practice.

These are the same skills that effective leaders rely on to build trust, coordinate departments, and implement change on a broader scale.

Field presence also increases your visibility and credibility — especially in the eyes of your supervisor.

Managers tend to value team members who show initiative, critical thinking, and observational skills.

If you want to explore potential job paths, check the full list of career opportunities in chemical engineering.

P&ID vs. PFD

Don’t confuse a P&ID with a Process Flow Diagram (PFD).

PFDs show the overall process in a simplified form, while P&IDs include all instrumentation, control logic, and safeguards required for detailed design and plant operation.

Field Experience: What to Do When Something Doesn’t Match in the P&IDs

As a process engineer, one of your most valuable tools is the P&ID (Piping and Instrumentation Diagram).

However, reality often reveals discrepancies—elements that are missing, installed differently, or simply outdated compared to what the drawings show.

When you encounter such a situation during field verification, you have two options:

1. Ignore It and Move On

You might think: “The plant is working fine. If no one has raised the issue so far, it’s probably not important.”

This attitude, although tempting, is risky and unprofessional, especially if the missing or mismatched component plays a safety or operational role.

2. Investigate and Take Action (the recommended path)

A responsible engineer takes the initiative to understand the issue. Here’s how:

Step 1: Verify

Double-check the latest version of the P&ID and confirm whether the discrepancy is indeed undocumented or just outdated information.

Step 2: Consult the HAZOP

If the missing component (e.g., a vent line, a pressure relief valve, an interlock, or a block valve) could be a safeguard, ask a Process Safety colleague to review the relevant HAZOP node with you. Was that protection considered in the risk assessment? Is it mentioned as a safeguard?

Step 3: Document Clearly

Take note of the exact location, equipment tag, drawing revision, and any relevant HAZOP references. Be precise and technical—this is not a casual observation but a potentially critical finding.

Step 4: Discuss Internally

Before raising it formally, validate your concern with a trusted technical peer. This helps refine your analysis and avoids unnecessary alarms.

Step 5: Communicate Professionally

If your concern is confirmed, inform your supervisor or the responsible process engineer. Do not just send an email listing the problem. Instead, propose a solution or at least outline possible options. The focus should be on improving plant safety and reliability—not placing blame.

How to Communicate Professionally (as a Process Engineer)

Technical competence is essential, but how you communicate your findings, ideas, or concerns can make the difference between being heard — or ignored.

Whether you’re reporting a mismatch in the P&IDs, suggesting a process improvement, or raising a safety concern, professional communication is key to being taken seriously and earning credibility.

Here’s how to approach it:

1. Be Clear and Factual

Avoid vague descriptions like “I think something’s wrong.”

Instead, say:

“During line tracing in Unit 200, I observed that the drain valve indicated in P&ID 200-PE-013 is not installed. This valve is listed as a safeguard in the HAZOP (Node 5, Deviation: Overpressure).”

Use tags, references, drawing numbers, and if applicable, quote risk assessment documents (HAZOP, LOPA, SIL). This shows that you are grounded in data, not in opinion.

2. Avoid Accusatory Language

You’re not there to point fingers. Avoid phrases like:

- “This was clearly a design mistake”

- “Somebody forgot to install it”

Instead, use neutral and constructive phrasing:

“This configuration may have changed after commissioning — it might be useful to review if this affects existing safeguards.”

This protects professional relationships and keeps the focus on solving the issue.

3. Propose, Don’t Just Point Out

Whenever possible, bring a suggestion, not just a problem.

“One option could be to verify whether a bypass line was installed during a MoC process. If the function is still required, installing a new valve or adapting the instrumentation could restore compliance.”

Being solution-oriented increases your value — and shows leadership potential.

4. Adapt to the Stakeholder

- If you’re speaking to operations, use practical language and link to process behavior.

- If you’re writing to management, highlight risk, compliance, and production impact.

- If it involves Process Safety, be technical and structured: show the logic, reference the safety studies, and suggest formal review.

Use the Right Channel

Some issues are best handled in person or in a short meeting, rather than via email.

Email may be permanent, but it’s not always effective for complex discussions.

When in doubt:

- Prepare a brief, structured summary (bullet points or 1-pager)

- Request a 15-minute discussion with your boss or safety lead

- Follow up with a short written recap

Conclusion

For a process engineer, the combination of technical curiosity and direct field experience is essential to grow and truly make an impact.

While the DCS control room provides a centralized view of operations, it is only through first-hand observation of the plant, critical analysis of the details, and engagement with those who operate the system daily that a complete understanding of the process can be developed.

Fostering curiosity and promoting field experience should be a priority for any organization aiming to improve plant reliability and to develop capable, responsible, and authoritative engineers.

Ing. Ivet Miranda

⬆️ Back to TopOther Articles You May Find Useful

- Chemical Engineering Principles Explained

- Unit Operations for Chemical Engineers

- First Law of Thermodynamics

- What is the Process of Distilling Water?

- VSD Pump Level Control for Decarbonization

- Engineering Problem-Solving in 7 Steps

FAQ

What are the most important engineering skills?

From my experience as a process engineer, the most important skill is communication.

What skills does a process engineer need?

A process engineer needs a mix of technical skills—like process design, data analysis, and understanding P&IDs—and soft skills such as communication, problem solving, and teamwork. Field awareness and the ability to explain complex ideas clearly are key to success in real plant environments.

Hard vs soft skills for engineers

Hard skills are technical abilities like process design, data analysis, and reading P&IDs.

Soft skills include communication, problem solving, and teamwork.

Both are essential — hard skills get you hired, soft skills help you grow.

Why is field experience important for engineers?

Field experience is essential for engineers because it turns theoretical knowledge into real technical judgment. In the field, you learn how equipment actually performs under changing conditions, how operators interpret procedures, and how small deviations can impact safety or product quality. It teaches you to connect drawings, DCS trends, and physical behavior — something no simulation can fully replicate.