Control Valve Leak and System Behavior

In industrial plants, control valves are used to regulate the flow of fluids and energy during normal operation. However, a control valve does not provide tight isolation: even when it is closed, a certain amount of internal leakage may still occur.

In most operating conditions, control valve leak is negligible. In specific system layouts, however, leakage can become relevant because it allows fluid or energy to pass downstream when the process does not require it.

In these situations, the issue is not the valve itself, but the path available to the leakage. For this reason, valve positioning can significantly influence system behavior during standby, shutdown, or maintenance conditions.

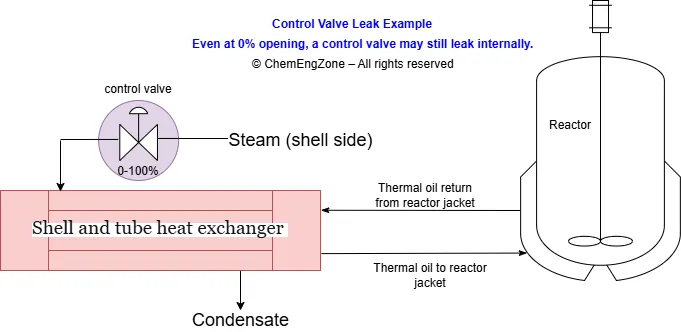

The following example illustrates how control valve leak can lead to unintended effects and why additional isolation may be required in certain configurations.

Control Valve Leak Example in a Heating System

Consider a typical heating system where steam is used as a utility to transfer heat to a secondary circuit through a shell-and-tube heat exchanger. In this configuration, steam flow is regulated by a modulating control valve installed upstream of the exchanger.

Under normal operation, the control valve adjusts steam flow to achieve the required heat duty. When heating is not required, the valve is driven to the closed position (0% opening), and the system is assumed to be isolated from the steam source.

However, as shown in the example, a control valve is not a tight shut-off device. Even at 0% opening, a small amount of steam may still pass through the valve due to internal leakage.

If a downstream heat transfer path exists — such as a heat exchanger permanently connected to a thermal oil or reactor jacket circuit — this leakage can result in unintended heat transfer. In practice, this means that the secondary circuit may start warming up even though no heating demand is present.

Control Valve Leak: Shutdown and Maintenance Risks

In many systems, the effects of control valve leak are not apparent during normal operation, when steam flow is actively regulated and heat demand is present. Under these conditions, small amounts of internal leakage are typically masked by the overall operating regime.

The situation changes during non-operating phases such as standby, shutdown, or maintenance, when the system is expected to be fully isolated from the utility source and no heat transfer is intended.

In these conditions, even a limited amount of steam leaking through a closed control valve can lead to unintended energy transfer. Downstream equipment may slowly warm up, thermal circuits may deviate from expected temperatures, or pressure may build up in parts of the system that are assumed to be depressurized.

Because these effects develop gradually, they are often not immediately noticed. However, they can alter initial conditions before start-up, interfere with maintenance activities, or create unsafe situations if not properly accounted for.

For this reason, control valve leak should not be evaluated only under steady-state operating conditions, but also in terms of how the system behaves when no heat input is required.

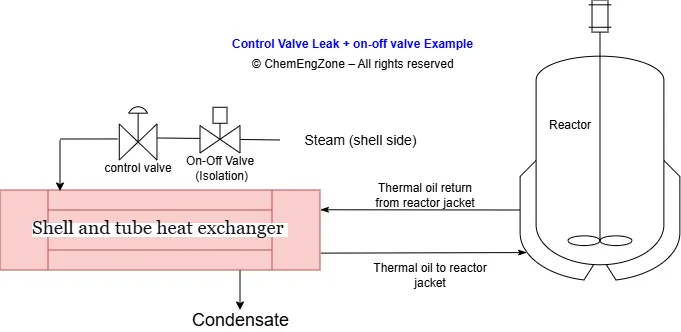

Why an Upstream On-Off Valve Is Required

When control valve leak can lead to unintended energy transfer, an additional isolation barrier becomes necessary. In these cases, the function of an on-off valve is not flow regulation, but true isolation from the utility source.

Placing the on-off valve upstream of the control valve allows the steam supply to be fully isolated whenever heat transfer is not required. When the on-off valve is closed, the downstream system is effectively separated from the energy source, and any internal leakage through the control valve can no longer feed the equipment.

This arrangement is particularly important during standby, shutdown, and maintenance conditions, when the system is assumed to be de-energized. A control valve alone cannot guarantee this condition, as it is not designed to provide tight shut-off.

From a maintenance perspective, the upstream on-off valve is essential. It provides a reliable means to isolate the control valve itself from the steam source, allowing safe intervention on the valve, actuator, or associated piping without relying on the internal tightness of the control valve.

In this configuration — source, on-off valve, control valve, and downstream equipment — the on-off valve acts as the primary isolation device, while the control valve retains its intended role of regulating flow during normal operation.

Conclusion

Control valve leak is not a failure, but an inherent characteristic of modulating valves.

Whether this leakage is irrelevant or becomes an operating issue depends entirely on the system configuration and on what the plant is expected to do outside normal operation.

For a process engineer, the key question is not whether a valve leaks, but where that leakage can go under standby, shutdown, or maintenance conditions.

That distinction is often what separates a correct design on paper from a system that behaves as intended in the field.

Ing. Ivet Miranda

⬆️ Back to TopControl Valve Leak – Engineering Check

Under which condition does a control valve leak become a real operating issue in a steam heating system?

Other Articles You May Find Useful

• Safety Interlocks: P&ID Example

• What Is HAZOP Analysis? Example and Template

• Vacuum Tank Collapse in Atmospheric Tanks

• Pressure Safety Valve vs Rupture Disc: Key Differences

FAQ

What is control valve leakage?

Control valve leakage refers to the small amount of fluid that passes through the valve seat even when the valve is in the fully closed position. It is a normal characteristic for most modulating valves and depends on the valve’s design and shut-off class.

Why do control valves leak even when closed?

Unlike on–off valves (such as ball or gate valves), control valves are designed for precise throttling rather than tight isolation. Their seat construction, actuator force, and trim type allow small clearances that cause minimal internal leakage when closed.

How can control valve leakage affect a process?

Even small leakage can maintain flow through a line, preventing full isolation during maintenance or creating unsafe conditions in batch or reactive systems. In pressure control loops, leakage may also cause pressure drift or loss of containment during shutdowns.