Safety Implications of Vacuum Tank Collapse

In thin-walled atmospheric storage tanks, even a pressure differential in the order of 50–100 mbar may be sufficient to trigger buckling instability, depending on geometry, wall thickness, and construction details.

Vacuum-related failures are often overlooked during design reviews because they are perceived as unlikely. When they occur, however, the resulting compressive instability can lead to sudden structural collapse, interrupting production and creating severe safety hazards.

Unlike corrosion, which progresses gradually, underpressure failures are immediate and total.

Example: Atmospheric Tank and Vacuum Risk

Many atmospheric storage tanks are protected against overpressure but not explicitly designed for vacuum. In such cases, loss of blanketing or vent restrictions can create underpressure conditions that were never considered in the original mechanical design.

For certain process vessels, vacuum protection is explicitly required by design.

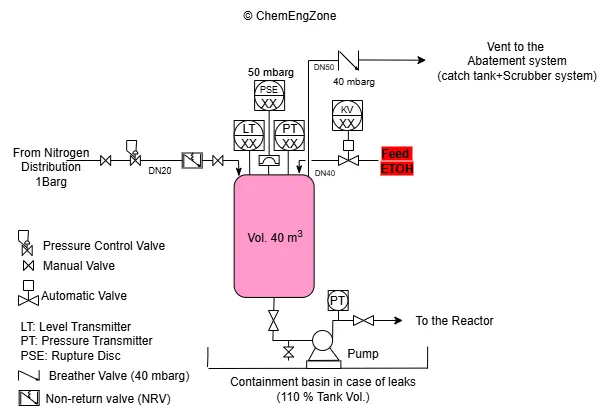

The critical question arises when evaluating an atmospheric storage tank such as the one shown below.

This configuration represents a typical scenario in which vacuum risk may not be immediately identified as a credible deviation during early hazard analysis.

The tank stores flammable solvent and is equipped with a rupture disc (PSE) set at 50 mbar(g) for overpressure protection, while a breather valve operates at 40 mbar(g) on the pressure side.

Should this atmospheric tank be specified for full vacuum service? Vacuum-resistant construction increases cost and mechanical complexity and is therefore often excluded unless a clear underpressure scenario is identified.

In this case, underpressure may develop due to loss of nitrogen blanketing during transfer or emptying, malfunction of the inerting system, or temperature variations causing vapor contraction.

If collapse occurs, structural failure can lead to release of flammable material and escalation scenarios such as flash fire or vapor cloud explosion (VCE) in ATEX-classified areas.

For this reason, HAZOP studies must assess the reliability of inerting systems and consider dedicated vacuum protection, including bidirectional rupture discs or full vacuum design where justified.

Design Considerations

Vacuum tank design requires systematic evaluation of all operating and transient conditions that may generate underpressure.

Typical scenarios include steam-out followed by rapid cooling, nitrogen inerting, draining of heated liquids, and jacket operation capable of inducing sudden internal pressure reduction.

For this reason, tanks exposed to such conditions should be specified for full vacuum service or equipped with reliable vacuum relief devices.

In many industrial applications, the cost of structural reinforcement or protection systems is significantly lower than the financial and safety consequences of a collapse.

While the previous example illustrates a specific configuration, vacuum risk must be assessed more broadly at the design stage.

Tanks and Pressure Regulations

As shown in the previous example, many storage tanks operate essentially at atmospheric pressure, with only a slight nitrogen blanketing, often below 50 mbar(g).

From a regulatory standpoint, equipment with a maximum allowable pressure not exceeding 0.5 barg falls outside the scope of the Pressure Equipment Directive (PED 2014/68/EU). Outside the European Economic Area, other pressure regulations apply (such as ASME BPVC or country-specific codes).

However, this does not eliminate the risk of collapse. Both atmospheric and low-pressure tanks are structurally weak and highly vulnerable to underpressure. If they are not designed for vacuum, even a small pressure differential can lead to buckling. The same applies to thin-walled process vessels in multipurpose plants.

Standards such as API 2000 require that these tanks are protected against both overpressure and vacuum.

In practice, loss of nitrogen supply during transfer or blocked vents can generate an underpressure strong enough to cause failure. For this reason, breather valves, vacuum breakers, or rupture discs specifically designed for vacuum protection are installed as safeguards.

Conclusion

Vacuum scenarios should always be explicitly discussed during design reviews and HAZOP studies sessions, even for equipment formally classified as atmospheric.

Operating conditions such as temperature changes, inerting, draining, or cleaning can easily generate underpressure levels capable of compromising structurally weak vessels.

Anticipating these scenarios during design and hazard reviews is the only effective way to define and implement safeguards before a failure occurs.

Ing. Ivet Miranda

Atmospheric Tank Vacuum Risk Quiz

Which situation is most likely to generate vacuum conditions in an atmospheric tank not designed for external pressure?

Other Articles You May Find Useful

• Pressure Safety Valve vs Rupture Disc: Key Differences

• Rupture Disc Installation: Where to Place It

• Vent Header Design: Safer Top Tie-In Layout

• Control Valve Leak and System Isolation

• What Is HAZOP Analysis? Example and Template

FAQ

What is a vacuum tank?

A vacuum tank is a vessel specifically designed to operate under negative pressure or partial vacuum. It is commonly used in applications such as degassing, drying, solvent recovery, or chemical processing. Unlike standard atmospheric tanks, vacuum-rated tanks are structurally reinforced to resist external pressure and prevent collapse during vacuum operation.

Are all storage tanks suitable for vacuum conditions?

No. Most atmospheric storage tanks are not suitable for vacuum because they lack the structural reinforcement needed to resist external pressure. Before reusing a tank in any operation that may generate vacuum, always verify whether it was designed or upgraded for vacuum service.

How many types of industrial tanks exist?

Industrial tanks can be broadly classified as follows:

Atmospheric tanks – Designed for near-ambient pressure. Not suitable for vacuum or pressure unless specifically protected.

Vacuum-rated tanks – Reinforced to withstand external pressure when vacuum conditions may occur.

Pressure vessels – Designed for internal pressures above atmospheric.

Jacketed tanks – Equipped with heating or cooling jackets for temperature control.

Underground tanks – Used for storage below grade, often with double containment.

Transport tanks – Mounted on trucks or trailers for liquid transfer.

Each category is designed according to specific standards, depending on operating pressure, service conditions, and safety requirements.