Tray efficiency in a distillation column is never 100%. Factors like liquid maldistribution, weeping, entrainment, and froth regime can significantly lower the efficiency. Understanding these limits is essential to optimize separation performance in real plants.

Tray Efficiency in columns

When you walk near a distillation column, it’s easy to forget that its efficiency doesn’t just depend on thermodynamics, it also depends on hydraulic behavior, liquid level, and how well each tray is leveled.

In tray columns — widely used in mass transfer processes such as distillation and absorption, a crucial performance parameter is tray efficiency. On it depend the actual column size, the energy required for the process, and the purity of the final product.

However, tray efficiency is not a fixed value: it is strongly influenced by the hydraulic behavior inside the column. Depending on operating conditions, the liquid–vapor contact can take different forms.

In the froth regime, a stable foam layer dominates; in the spray regime, the liquid breaks into fine droplets; in the emulsion regime, turbulence and mixing prevail. Each regime modifies how effectively mass transfer occurs, directly impacting tray efficiency.

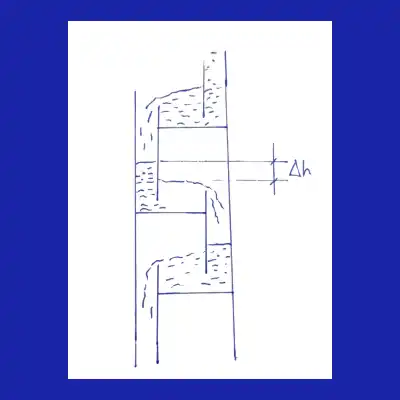

The schematic below (Fig. 1) illustrates how liquid overflows from one tray to the next, with Δh indicating the liquid height difference maintained by the weir.

🧠 Quiz: What happens if the liquid head Δh on a distillation tray is too low?

Show Answer

Answer: Weeping becomes more likely, reducing separation efficiency.

When Δh is too low, vapor passes through the perforations without enough liquid resistance. As a result, the vapor–liquid contact time decreases, reducing mass transfer and overall column performance. The column may then require more trays or a higher reflux ratio to reach the same product purity.

Design Tip: During column design, ensure the weir height and liquid head are sufficient to maintain a stable froth layer. Typical weir heights range from 25–65 mm, with an additional 10–30 mm of liquid head, for a total liquid depth of roughly 40–80 mm on each tray. These values provide a good balance between pressure drop and liquid stability.

Always verify these parameters using standard design references such as Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook or Seader & Henley – Separation Process Principles, as optimal ranges may vary with system properties and operating conditions.

In practice, weir heights are usually in the range of 25–65 mm, with the liquid head adding another 10–30 mm, so that the total liquid depth on a tray is often around 40–80 mm.

This seemingly small parameter is fundamental because it controls how the liquid spreads across the tray surface before passing to the lower stage. If Δh is too low, weeping is more likely to occur; if it is too high, the pressure drop increases and the risk of flooding rises. In both cases, tray efficiency is directly affected.

As highlighted in Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook, practical variables such as liquid distribution, weir geometry, and tray spacing are decisive for real performance.

Undesired phenomena such as weeping (liquid leaking through perforations) and entrainment (droplets carried upward with vapor) also play a key role.

📘 Download the FREE PDF: Trays Column vs Packed Column

Get a two-page practical summary comparing trays column and packed column. Learn the differences in efficiency, pressure drop, operational flexibility, typical uses, and maintenance. Perfect for engineers and students who want to fix the concept quickly and simply.

How Tray Efficiency Is Defined (Murphree Concept)

In column design, tray efficiency is often expressed as Murphree efficiency. It is defined as the ratio between the actual change in vapor composition across a tray and the change that would occur if the vapor leaving the tray were in equilibrium with the liquid on that tray.

This definition is widely used because it links the theoretical concept of equilibrium stages to the real performance of physical trays. However, in non-ideal hydraulic regimes such as the spray regime, Murphree efficiency can drop significantly due to entrainment and maldistribution, making the gap between design predictions and actual plant performance more evident.

In plant operation, this means that even with a theoretically well-designed column, an uneven liquid flow or a poorly leveled tray can drastically reduce separation efficiency.

Fig. 2 shows a misaligned tray inside a distillation column. When a tray is not properly leveled, the liquid distribution becomes uneven: one side accumulates excessive liquid while the opposite side remains partially dry. This imbalance reduces the active contact area between vapor and liquid, creating zones of low mass transfer and ultimately lowering tray efficiency.

This example highlights a crucial point: even small mechanical issues, such as improper leveling during installation or thermal expansion during operation, can have a measurable impact on efficiency.

Conclusion

As the study demonstrated, the spray regime is especially unforgiving: entrainment can quickly erode efficiency and even trigger premature flooding. Yet, relatively small design adjustments—such as blocked weirs, improved feed handling, or switching to fixed-valve trays—can deliver significant gains, sometimes with immediate economic payback.

For engineers in the field, the lesson is clear: tray efficiency is never a fixed number. It must be actively protected through careful design, proper installation, and ongoing operational checks. Bridging the gap between theory and plant reality is what ensures that a column not only meets its separation target, but does so reliably and efficiently over time.

Ing. Ivet Miranda

⬆️ Back to TopOther Articles You May Find Useful

• How Distillation Works: Engineering Explanation

• Unit Operations in Chemical Engineering: Types and Examples

• What is Heat Transfer? Definition and Types

• Chemical Engineering Core Disciplines – A Practical Overview

Technical References

- Perry, R. H., Green, D. W., & Southard, M. Z. (Eds.). Perry’s Chemical Engineers’ Handbook, 9th Edition. McGraw-Hill Education, 2019 – Chapter 14: Distillation.

- Seader, J. D., Henley, E. J., & Roper, D. K. Separation Process Principles, 4th Edition. Wiley, 2016 – Chapter 9: Plate and Packed Columns.

- Aryan, Aadam. “Hydrodynamic Performance of Spray Regime Trays: Efficiency and Entrainment Analysis.” Distillation Equipment Company Ltd, Technical Report, 2022.

- Kister, H. Z. Distillation Operation. McGraw-Hill, 1990 – Section 3.3: Tray Efficiency and Hydraulic Regimes.

FAQ

What causes low tray efficiency in distillation columns?

Low tray efficiency is often linked to hydraulic issues such as weeping, entrainment, or flooding. Mechanical problems like misaligned trays or poor liquid distribution can also reduce the effective contact area between vapor and liquid.

How can tray efficiency be improved?

Improvements can come from design choices (longer flow path length, blocked weirs, fixed-valve trays) as well as operational adjustments (better feed distribution, proper tray leveling). Even small changes can lead to measurable efficiency gains.

Is tray efficiency the same as stage efficiency?

Not exactly. Stage efficiency is a theoretical concept, while tray efficiency refers to the actual performance of a physical tray. In practice, tray efficiency is what links the number of theoretical stages to the real number of trays required.

Does tray efficiency reach 100% in practice?

No. Tray efficiency never reaches 100%. Even under ideal conditions, some vapor bypasses liquid and some liquid bypasses vapor. Typical efficiencies range from 50% to 80%, depending on the system and operating regime.