Thermodynamics Work Meaning

As introduced in Joule’s Experiment & 1st Law of Thermodynamics, work appears in the energy balance as one of the two modes of energy transfer, together with heat.

However, while the First Law establishes the conservation of energy, it does not define how work is mechanically evaluated during a transformation. This article focuses on the physical definition and calculation of thermodynamic work.

Historically, thermodynamics was first developed using ideal gases, because they provide a simple and consistent relationship between pressure, volume, and temperature. This framework allowed the derivation of fundamental laws and the geometric interpretation of mechanical work before extending the analysis to real substances.

For this reason, the classical treatment of thermodynamic work begins with closed systems of ideal gases and piston–cylinder configurations.

Work in a Piston–Cylinder System

During a thermodynamic transformation, if the volume increases the system performs work on the surroundings, while a decrease in volume implies that work is done on the system.

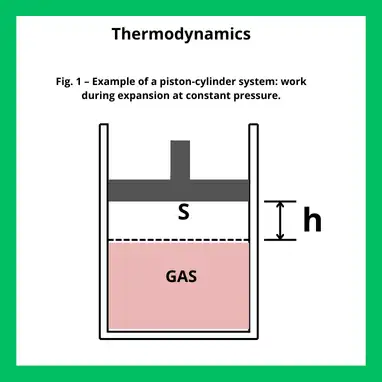

Consider a cylinder containing a fixed amount of gas and equipped with a movable piston of area S. At the initial state, the system is in mechanical equilibrium, meaning the gas pressure equals the external pressure acting on the piston.

Keeping the pressure constant, we increase the temperature so that the piston rises by a height h. As a result, the volume changes by:

ΔV=V2−V1=S⋅h

The force exerted by the gas on the piston is P⋅S, and it acts in the same direction as the displacement.

The positive work done by the gas during the expansion is therefore: W=P⋅S⋅h=P⋅ΔV

Where:

- P = pressure [Pa]

- S = cross-sectional area of the piston [m²]

- h = displacement of the piston [m]

- ΔV=S⋅h = change in volume [m³]

- W = work done by the gas [J]

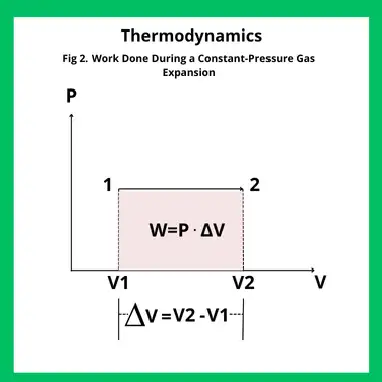

This concept can be represented graphically using a pressure–volume diagram.

When the pressure remains constant, the work corresponds to the area under the horizontal line at pressure P, between the initial and final volumes.

As shown in Figure 2, the work is given by: W=P⋅ΔV=P⋅(V2−V1)

In a P–V diagram, thermodynamic work is not read from a formula but from geometry. The work exchanged during a transformation corresponds to the area under the P–V curve, which gives a direct physical interpretation of expansion and compression processes.

This expression confirms that, under constant pressure, the area of the rectangle in the P–V diagram directly represents the mechanical work exchanged.

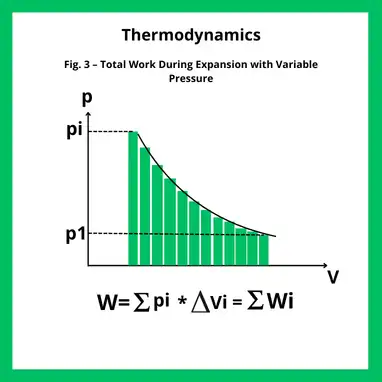

When the pressure varies during the transformation, the work can no longer be determined using a single value of P.

In this case, the process is viewed as a sequence of small steps, each with an approximately constant pressure Pi (Fig. 3). For each small volume change ΔVi , the elementary work is: Wi=Pi⋅ΔVi

The total work over the transformation is obtained by summing all contributions: W=∑Pi⋅ΔVi

In the limit of infinitesimally small steps, the sum becomes the integral: W=∫V1V2P(V) dV

Graphically, this corresponds to the area under the curve in the pressure–volume diagram, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Work in a Thermodynamic Cycle (PV Diagram Explained)

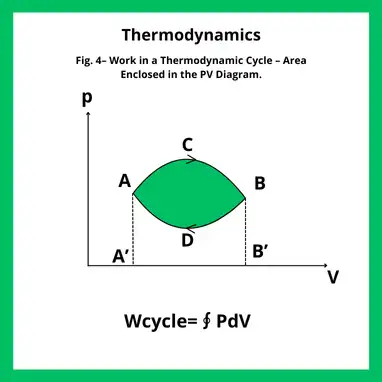

In a cyclic transformation, the system undergoes a sequence of processes and eventually returns to its initial state. Since the initial and final states coincide, the net change in internal energy over the cycle is zero, and the net work equals the net heat exchanged.

Although the First Law establishes this energy balance, the feasibility and efficiency limits of cyclic devices are determined by the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which introduces entropy generation and irreversibility as fundamental constraints.

In a pressure–volume diagram, the work of a complete cycle corresponds to the area enclosed by the path. The sign depends on the direction of traversal:

- If the cycle is traversed in the clockwise direction, the system performs work on the surroundings: Wnet>0

- If the cycle is counterclockwise, the surroundings do work on the system: Wnet<0

This distinction is fundamental in thermodynamic devices: heat engines operate clockwise, while refrigeration and heat pump cycles operate counterclockwise.

Figure 4 illustrates this concept. Along the upper path (A → C → B) the gas expands and performs positive work, while along the lower path (B → D → A) it is compressed and the work is negative. The difference between these contributions corresponds to the area enclosed by the cycle.

For ideal gases, the work associated with a reversible transformation can be calculated analytically using the following expressions.

Conclusion

Mechanical work represents the operational form of energy transfer in thermodynamic systems. Through the relation W=∫PdV, work acquires a clear geometric and physical interpretation in the P–V diagram.

While the First Law defines work within the energy balance, and the Second Law sets limits on the performance of cyclic devices, the evaluation of work itself depends on the transformation path and the pressure–volume relationship.

For a structured overview of how work integrates within the complete thermodynamic framework, see Meaning of the 4 Laws of Thermodynamics.

Ing. Ivet Miranda

Thermodynamics Work Quiz

In a closed system undergoing a thermodynamic transformation, what determines the amount of work exchanged?

Other Articles You May Find Useful

First Law of Thermodynamics and Joule Experiment

Second Law of Thermodynamics: No Perpetual Motion

Chemical Engineering Principles Explained

Unit Operations: A Practical Introduction for Engineers

Heat Transfer Basics for Engineers

Heat Exchanger Fouling and Rubby Formation

Career Opportunities in Chemical Engineering

Vacuum Tank Collapse: Hazards & Prevention

FAQ

What is reversible work in thermodynamics?

Reversible work is the maximum possible work obtained from a process carried out infinitely slowly, with the system in equilibrium at every stage. It is represented by the exact area under the curve in the P–V diagram.

How many laws of thermodynamics are there?

There are four fundamental laws: Zeroth, First, Second, and Third Law of Thermodynamics. Some formulations also mention a “Fourth Law” in modern contexts, but the first four are universally accepted.

Is thermodynamics a theory?

Thermodynamics is not just a theory; it is a set of experimentally validated laws (Zeroth, First, Second, Third Law) that describe how energy is conserved and transformed.

Is thermodynamics physics or chemistry?

Thermodynamics is a fundamental branch of physics, but it is also applied in chemistry, engineering, and materials science. It studies energy transformations in all these contexts.