Why Heat Transfer Is a Core Unit Operation in Chemical Engineering

Heat transfer is one of the fundamental unit operations in chemical engineering because temperature directly influences reaction kinetics, phase equilibrium, and material properties.

In industrial plants, thermal energy must be added, removed, or redistributed at almost every stage of the process. Distillation requires vaporization and condensation. Reactors require temperature control to maintain selectivity and avoid thermal runaway. Crystallizers and dryers depend on controlled heat removal.

From a design perspective, heat transfer determines:

– equipment size

– energy consumption

– operating stability

– safety margins

Unlike purely mechanical operations, heat transfer affects both thermodynamics and process control. For this reason, it plays a central role in plant design and operation.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Heat Transfer

Heat transfer occurs through three fundamental physical mechanisms: conduction, convection, and radiation. In real industrial systems, these mechanisms rarely act in isolation; they interact under specific boundary conditions and material constraints.

Conduction

Conduction is the transfer of thermal energy through a solid or a stationary fluid due to a temperature gradient. At the microscopic level, energy is transmitted through molecular vibration and electron interaction. In engineering calculations, conductive heat transfer is described by Fourier’s law, which relates heat flux to the temperature gradient and thermal conductivity of the material.

Convection

Convection involves heat transfer between a surface and a moving fluid. It combines conduction at the interface with bulk fluid motion. In industrial applications, convection is typically forced (pumps, fans, flow circulation), and its intensity depends on flow regime, fluid properties, and geometry.

Radiation

Radiation is the transfer of energy through electromagnetic waves and does not require a physical medium. While often negligible at low temperatures, radiative heat transfer becomes significant in high-temperature processes such as furnaces and combustion systems.

Industrial heat transfer equipment is designed by combining these mechanisms in controlled geometries, where conduction through walls, convection in fluids, and, in some cases, radiation act simultaneously.

Driving Force and Energy Balance in Heat Transfer

Heat transfer does not occur spontaneously without a driving force.

The fundamental driving force for heat transfer is temperature difference.

Thermal energy flows from a region at higher temperature to a region at lower temperature until equilibrium is reached. The rate at which this transfer occurs depends on both the temperature gradient and the ability of the system to transport energy.

In process engineering, the total heat transferred — often called heat duty — is linked to the energy balance of the system. For a flowing stream, the simplest expression is:

Q = ṁ Cp ΔT

where Q represents the heat duty, ṁ the mass flow rate, Cp the heat capacity, and ΔT the temperature change of the fluid.

This relationship highlights a fundamental principle: heat transfer is not only governed by temperature difference, but also by the thermal capacity rate of the interacting systems.

In real equipment, the temperature difference is not uniform along the surface. For this reason, design calculations require appropriate treatment of the temperature profile across the exchanger.

Main Industrial Heat Transfer Configurations

In industrial plants, heat transfer is implemented according to process objectives and operating constraints. The chosen configuration depends on temperature levels, pressure conditions, controllability requirements, and long-term reliability considerations.

From a practical standpoint, three main configurations are commonly adopted.

Process-to-Process Heat Exchange

In process-to-process heat exchange, thermal energy is transferred directly between two process streams. One stream is cooled while the other is heated.

This configuration is widely used to improve energy efficiency and reduce utility consumption. Typical examples include feed preheating using hot reactor effluent, or heat recovery between column streams.

From a design perspective, this approach requires:

– compatible pressure levels

– acceptable contamination risk

– stable operating conditions

Process-to-process exchange plays a key role in heat integration strategies and energy optimization.

Utility-Based Heat Transfer

In this configuration, thermal energy is exchanged between a process stream and an external utility such as steam, cooling water, thermal oil, or refrigerant.

Utilities provide stable and predictable temperature levels that are largely independent of process-side variability. For this reason, utility-based heat transfer is essential for:

– reactor temperature control

– reboilers and condensers

– cooling duties requiring tight temperature regulation

Although these systems are generally easier to control, they increase utility demand and therefore impact overall operating cost.

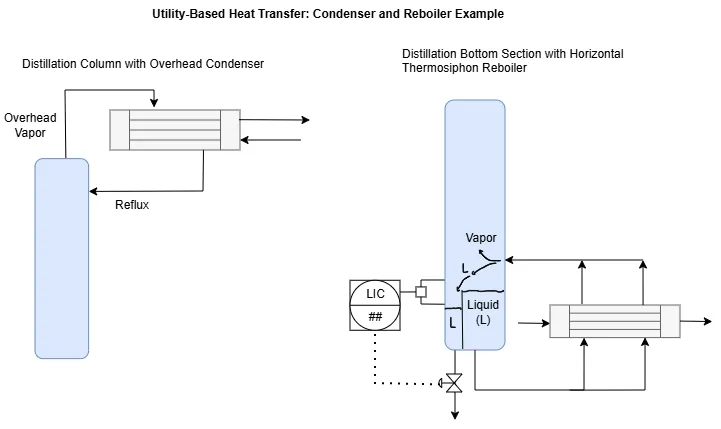

The example above shows two distillation columns: one equipped with an overhead condenser and the other with a horizontal thermosiphon reboiler, both representing typical applications of utility-based heat transfer.

Heat Transfer Integrated into Process Equipment

In many cases, heat transfer is not handled by a separate exchanger but integrated directly into process equipment.

Examples include:

– jacketed reactors

– internal coils

– double-pipe sections

– heated tanks

In these systems, thermal control is structurally embedded into the equipment design. This configuration improves compactness and controllability but may limit flexibility compared to external exchangers.

Engineering Criteria for Selecting a Heat Transfer Configuration

Selecting a heat transfer configuration is not a purely theoretical decision.

It is an engineering choice driven by process requirements, operating constraints, and economic considerations.

The first determining factor is the required heat duty. The magnitude of the energy exchange defines whether the solution can be integrated into existing equipment or requires a dedicated heat exchanger.

Temperature level is equally critical. The available temperature difference between the process stream and the heating or cooling medium determines feasibility. Small temperature approaches may require larger surface areas or alternative configurations.

Pressure constraints must also be evaluated. High-pressure systems often dictate specific exchanger types and mechanical designs, directly influencing material selection and construction standards.

The presence of phase change is another key parameter. Condensation and boiling provide high heat transfer coefficients, but they also introduce stability and control challenges that must be addressed in the design.

Controllability plays a central role in reactive or highly sensitive processes. Systems requiring tight temperature regulation may favor utility-based configurations, where energy input can be adjusted rapidly and predictably.

Fouling tendency and maintenance accessibility cannot be overlooked. Fluids prone to scaling, polymerization, or particulate deposition influence the selection of exchanger geometry and cleaning strategy.

Finally, the economic balance between capital investment and operating cost must be considered. A configuration with higher efficiency may reduce utility consumption but require greater initial investment.

For these reasons, heat transfer configuration selection is a multidimensional engineering decision rather than a simple equipment choice.

From Heat Transfer Principles to Equipment Design

Once the appropriate configuration has been selected, the focus shifts from conceptual decision-making to quantitative design.

At this stage, the engineer must convert thermal requirements into measurable parameters: heat transfer area, temperature profiles, pressure drop, and material compatibility.

Unlike the initial configuration choice, which is strategic, equipment design is analytical. It involves applying heat transfer correlations, evaluating boundary conditions, and verifying mechanical constraints.

This transition from principles to calculation marks the difference between understanding heat transfer and engineering it.

The detailed methodology for sizing exchangers, evaluating reboiler performance, and assessing integrated heat transfer systems is explored in the dedicated technical articles within this section.

Conclusion

Heat transfer is therefore not only a physical phenomenon but a governing principle in process engineering. From reaction control to phase separation and energy recovery, temperature management defines performance, efficiency, and safety margins in industrial plants.

Among industrial heat transfer equipment, shell-and-tube exchangers represent one of the most widely used and versatile solutions. Their construction, flow arrangements, and design criteria are examined in detail in the dedicated article on Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger Design.

Ing. Ivet Miranda

Other Articles You May Find Useful

• Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger Design

• Heat Exchanger Fouling and Rubby Formation

• Unit Operations in Chemical Engineering: Types and Examples

• The 4 Laws of Thermodynamics

FAQ

What is process-to-process heat exchange?

Process-to-process heat exchange is the transfer of thermal energy between two process streams within the same plant. One stream is cooled while the other is heated, enabling energy recovery and reducing the demand for external utilities. Typical equipment includes shell-and-tube, plate, and double-pipe heat exchangers.

When is utility-based heat exchange preferred over process-to-process exchange?

Utility-based heat exchange is preferred when no suitable process stream is available for energy recovery or when precise temperature control is required. Utilities such as steam, cooling water, or thermal oil provide flexibility, operational safety, and easy integration with centralized plant utility systems.

How is heat transfer integrated into process equipment?

In process equipment such as reactors, crystallizers, dryers, or storage tanks, heat transfer is achieved through external jackets or internal coils. These systems are designed to ensure temperature control and uniformity, prioritizing process stability and safety over maximum thermal efficiency.